July 10

Ah, yes: James Abbott McNeil Whistler was born on this date in 1834, although, rather splendidly for such a legendarily disputatious and controversial man, some sources argue for tomorrow.

The better-qualified can continue to debate exactly how good an artist Whistler was. I wonder at his capacity for a quarrel; the remarkable wit; his unswerving devotion to the outré life of the artist; and the resilience, even obstinacy, with which he argued ‘Art for Art’s Sake’ over all other consideration and no matter how redoubtable the opponent, Ruskin, Wilde or whoever. But this was the man who said, ‘People will forgive anything but beauty and talent. So I am doubly unpardonable’.

Before giving you some Whistler stories, I have two fascinating facts to submit: the Commander of West Point Military Academy, which he entered in slightly unlikely fashion in 1851, was Robert E Lee; and in 1866 he delivered torpedoes to Chile in its dispute with Spain.

Someone annoyed by Whistler’s self-regard said to him, ‘It’s a good thing we can’t see ourselves as others see us.’‘Isn’t it?’ replied Whistler. ‘I know in my case I would become terribly conceited.’

To the woman who told him the view of the Thames that morning had been exquisite, with a marvellous haze that reminded her of Whistler’s paintings: ‘Yes, madam, Nature is creeping up.’

Whistler was printing some of his etchings with Walter Sickert, a great admirer and pupil. When Sickert dropped one of the plates, Whistler said, ‘How like you!’ A little later Whistler dropped a plate. ‘How unlike me!’ he said.

Lord Leighton: 'My dear Whistler, you leave your pictures in such a sketchy, unfinished state. Why don't you ever finish them?' Whistler: 'My dear Leighton, why do you ever begin yours?’.

And, for a change, one against him: he insisted on ordering for himself in a Paris restaurant, priding himself on his fluency in French. His companion attempted to correct him, to be told, ‘I am quite capable of ordering a meal in France without your assistance.’ ‘Of course you are,’ said his friend, ‘but I just distinctly heard you order a flight of steps’ (Presumably he was after an escalope rather than an escalier).

On y va!

July 11

Yes, another instalment in my ground-breaking series, Unexpected Other Occupations of the Rich and Famous! We have already had golfers, dentists and goalkeepers. Today, some odd bankers!

TS Eliot (Lloyds)

Kenneth Grahame (Bank of England)

Floella Benjamin (Barclays)

William Faulkner (First National Bank of Oxford, Miss.)

Paul Gauguin (La Bourse)

PG Wodehouse (Hongkong & Shanghai)

Kenneth Grahame’s was by some measure the most successful career. He rose to become secretary to the Bank of England, one of its five senior officers. But it was not without incident: in 1903, he was shot at three times in the Bank by a confused man later sent to Broadmoor. The shots all missed, allowing Grahame to write ‘The Wind in the Willows’.

But he also had the unsatisfactory sex life traditional to the classic children’s author with the daughter of the man who invented the pneumatic tyre. And, yet more sadly, he had, as well, the tragic child for whom the stories were written, who was killed under a train, as was the model for JM Barrie’s ‘Peter Pan’.

Wodehouse’s banking career was probably the least auspicious. In the first of his two years, he was late for work twenty times (excluding delays caused by fog [!]). He summed up his time in Lombard Street to the HSBC magazine thus: ‘If there was a moment in the course of my banking career when I had the remotest notion of what it was all about, I am unable to recall it. From Fixed Deposits I drifted to Inward Bills - no use asking me what Inward Bills are, I never found out….. My total inability to grasp what was going on made me something of a legend in the place’.

Contrast that with the cautious view in Lloyds on TS Eliot that, in time, with luck, ‘he might have made branch manager’.

Oh, and the short period Faulkner worked in a bank might have been yet shorter if it hadn’t been owned by his grandfather.

Paul Gauguin worked in Paris rather than at the Tahiti branch.

Floella Benjamin’s banking career in the 1960s never took off after she wore a trouser suit. And there was something else about her I can’t quite put my finger on:

Next customer!

July 12

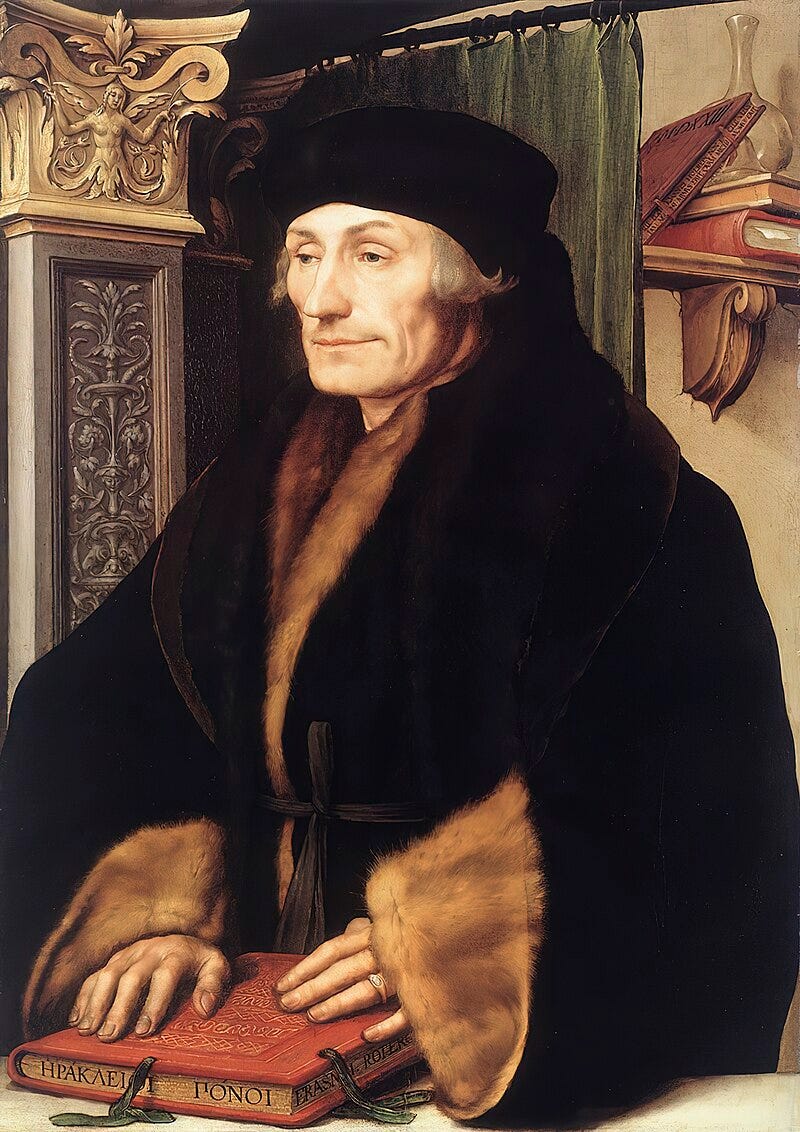

Erasmus of Rotterdam, that most wonderful philosopher, theologian, humorist, and human being splendidly aware of his faults and frailties, went to his eternal reward on this date in 1536.

His was the outstanding voice of tolerance, humanity and wisdom in a time lacking much of it as angry sides fought over, in the ultimate and lasting irony, the religion of peace.

As the Reformation seethed then raged, Erasmus, the committed Catholic if reluctant monk, pursued the thankless task that has befallen liberals before and ever since of trying to reason with the unreasonable.

He was rescued from despair by his faith, his wit, and his fame: the first writer to take advantage of the new printing press, he was known as the most famous man in Europe, even if his teachings were ignored.

The wit rings on. His mega best seller, ‘In Praise of Folly’, published in 1509, is described with feeling by Lord Clark (of Civilisation), a great admirer:

‘To an intelligent man, human beings and human institutions really are intolerably stupid and there are times when his pent-up feelings of impatience and annoyance can’t be contained any longer. Erasmus’s “Praise of Folly” was a dam-burst of this kind; it washed away everything: popes, kings, monks (of course), scholars, war, theology – the whole lot.’

A telling measure of the admiration he commanded is that he got away with it (and with being evidently gay, if celibate).

Here is further flavour of the man, starting with his response to a rebuke for not observing the Lenten fast: ‘I have a Catholic soul but a Lutheran stomach’.

And:

‘The chief element of happiness is this: to want to be what you are’.

‘There is no joy in possession without sharing’.

‘The highest form of bliss is living with a certain degree of folly.’

‘Many times what cannot be refuted by arguments can be parried by laughter’.

‘What else is the whole life of mortals, but a sort of comedy in which the various actors, disguised by costumes and masks, walk on and play each one’s part until the manager walks them off the stage?’

‘Now I believe I can hear the philosophers protesting that it can only be misery to live in folly, illusion, deception and ignorance. Nay, rather, this is to be a man.’

‘Picture the prince, such as most of them are today: a man ignorant of the law, well-nigh an enemy to his people's advantage, while intent on his personal convenience, a dedicated voluptuary, a hater of learning, freedom and truth, without a thought for the interests of his country, and measuring everything in terms of his own profit and desires.’

‘Man's mind is so formed that it is far more susceptible to falsehood than to truth’.

But hey, it’s only 500 years later.

What a lovely magpie’s-eye collection you offer up made, dear Charles. It’s rare not to find some rare, sparkling treasure in your pieces. Thank-you. More please, Ed