July 13

If you ever imagine things were much simpler in the Old Days, I would point you in the direction of the renowned Tudor figure, John Dee, born on this date in 1527.

To begin, what was Dee? All agree he was exceptionally gifted with the very finest academic mind. But it was what he did with it that presents the difficulty: too much. Dee was, by turns and often at once, a priest, mathematician, philosopher, geographer, historian, antiquarian, astrologer, diviner of treasure, an alchemist, and, oh, yes, a communicator with angels who he thought would help him understand, well, everything.

There was, of course, not the same conflict between those disciplines as there would be today. The distinction between the natural and supernatural was far less defined, allowing a much more tolerant view of attempts to discover it. I give you - rather later, too - Sir Isaac Newton and his alchemical interests. And some might argue the Enlightenment led to an unenlightened rejection of the inexplicable.

Dee’s problem was the too much thing. And a marvellous curiosity that led him to be just a little, how you say, gullible. He is most famous today for the magic, the alchemy and the angels, but he did tend to believe that his fellow toilers after eternal truth were as uninterested in venal matters as he. Principally, one Edward Kelley, a rogue of the very first water with a gift for fake mediumship - only he could talk to the angels and tell Dee what they said - that led the pair of them off round Europe promising gold and wisdom to far foreign courts.

In between, he worked out the auspicious astrological date for Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, drew maps for various North American voyages of exploration and claim-making based on another trusting belief of his in earlier highly unreliable historians claiming that if King Arthur hadn’t discovered North America, a Welsh prince called Madoc had.

I might go on, and tell you about how he thought that ancient Hebrew texts provided a crucial link between magic and the mathematical basis of nature. He also calculated, and please don’t ask me to explain, that there were 301,655,172 angels.

Or his search for the Philosopher’s Stone, the crucial substance that pulverised would produce gold. Remarkably enough, Edward Kelley dug up some on a Cotswolds hill along with a Viking scroll promising treasure, another abiding interest of the always cash-strapped Dee. And we certainly won’t dwell on an angel’s order to Kelley that universal harmony would be much improved if he and Dee had a wife-swapping session (Dee’s wife was young and pretty).

And none of it came to pass (well, apart from the wifely shenanigans). No gold, no North American riches or discoveries, no triumphant synthesis and revelation of the universe. Dee died in poverty, Kelley trying to escape from a castle in Bavaria where he had been imprisoned for once again failing to come up with the gold.

In 1642, a Lombard Street confectioner bought an old chest which (he eventually discovered) contained Dee’s angelic conversations and concomitant secrets of life in a concealed compartment. Unfortunately, the confectioner’s maid used many of the pages to line her pie tins. But, by almost wondrous means, the remnants reached Elias Ashmole, founder of the Ashmolean museum in Oxford.

Life, The Universe and Everything remain stubbornly unexplained. Nevertheless, it is the precious survivors of Dee’s antiquarian library, which held some 3,000 books collected by him from any number of sources all over Europe, then dispersed after his death, that are his true legacy.

July 14

Bastille Day, of course. But let us celebrate Englishness instead, as it is also the date in 1864 when Dr William Gilbert Grace scored his maiden century four days before his 16th birthday in the year that John Wisden’s ‘The Cricketer’s Almanack’ was first published.

The Doctor scored more than 120 centuries in his 44-year career, including ten double and three triple centuries. To schoolboys like me, he was the very model of a certain type of Englishman, effortlessly superior, as gracious as his name, standing for a time when Britain ruled the world wisely, fairly and confidently as its undeniable right and selfless burden.

Age does bring consolation, but not necessarily in the realisation that this country’s freebooting, grandstanding, profiteering and unasked-for but self-righteous administering requires just a touch more inconvenient nuance and honesty.

WG Grace stands as a remarkably fine symbol of all this. A wonderful cricketer, certainly; and kind to children. But also a cricketer who applied the rules to his advantage rather than in their spirit, and pretended to be a Gentleman when he was very much a Player. Another, possibly more prevalent, type of Englishman, the fiercely pragmatic ones who don’t play fair: The Black Prince, Henry Five, Drake, Cromwell, Clive, and so on, and on.

The Ashes, for example, are thought a historic, romantic kind of thing, the English lamenting and almost revelling in defeat to a colony, and undertaking, sportingly, to take cheerful revenge. Douglas Jardine’s later success by employing physical violence is generally the rejoinder to that; I wasn’t aware that the original defeat was fired and fuelled by Grace’s deliberate running-out of an Australian who believed play on that ball to be over and nodded the same to Grace before leaving his crease to tamp the pitch.

Indeed. Geoffrey Moorhouse, historian and sports writer, described Grace - in Wisden, no less - as a ‘shameless cheat’. It is certainly true that as a Gentleman, ie, amateur, he earned far more from the game, in appearance fees and such - as much as £1m in today’s money - than any Player, ie paid professional.

The stories of his bad behaviour on the pitch are legion. One will do: the nominally determinative Charles Kortright of Essex, a legendarily fast bowler, playing for Essex, had several clearly legitimate LBWs against Grace turned down by an umpire clearly influenced by his fame, equally intimidating stare and customary refusal to walk. Kortright then clean bowled him; as Grace walked away, he shouted after him, ‘You’re surely not going, Doctor? There’s a stump still standing’.

Something similar must surely also have occurred to many of Britain’s imperial subjects over the years.

Over!

July 15

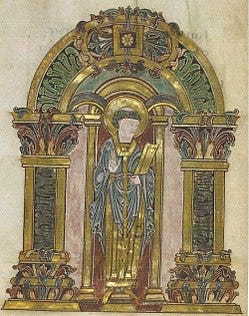

It rained heavily on this date in Winchester in 971 as they were translating the remains of the revered bishop, Swithin.

The humble holy man had asked to be laid to rest outside the old minster so that feet could tread and rain fall upon him. And there he lay for 108 years until his growing reputation for posthumously performing miracles of healing for the halt and the lame convinced the monks of the old minster that his remains should be transferred within.

The pouring rain that day was interpreted as a sign of the saint’s displeasure, and gave rise to the popular belief, ‘St Swithin’s Day if it do rain, for 40 days it will remain’. The miracles, however, continued in profusion, although the saint was known to appear in dreams warning that they might be discontinued; in 974 the monks prudently moved part of the body back outside and built a magnificent shrine over it.

Aelfric, later Bishop of Eynsham, was a monk at Winchester, and recalled the old church ‘hung around with crutches and stools of cripples from one end to the other on either wall’.

The monks had been ordered by their bishop to sing thanksgiving after every miracle; soon, they were having to get up four or five times a night to perform. Very tired, they began to slacken off a bit until the vexed saint appeared and issued another chiding. They got back to it and the miracles continued.

In 1093, the part remains within the old minster were moved once more, to the grand new Norman cathedral. Meanwhile, at some stage the saint’s head was taken to Canterbury and an arm to Peterborough. The shrine, with its magnificent gold, silver and bejewelled reliquary, survived until 1538 when the cult was officially ended by Henry VIII’s new Church of England and the shrine destroyed.

Remarkably, or not, there is a scientific basis to the 40 days: Around the beginning to middle of July, the jet stream settles into a pattern which continues to the end of August in seven or eight years out of ten. When the stream lies north of the British Isles, high pressure brings fine weather; south, low pressure brings rain.

Time to tap that barometer and check those galoshes, I should have said.